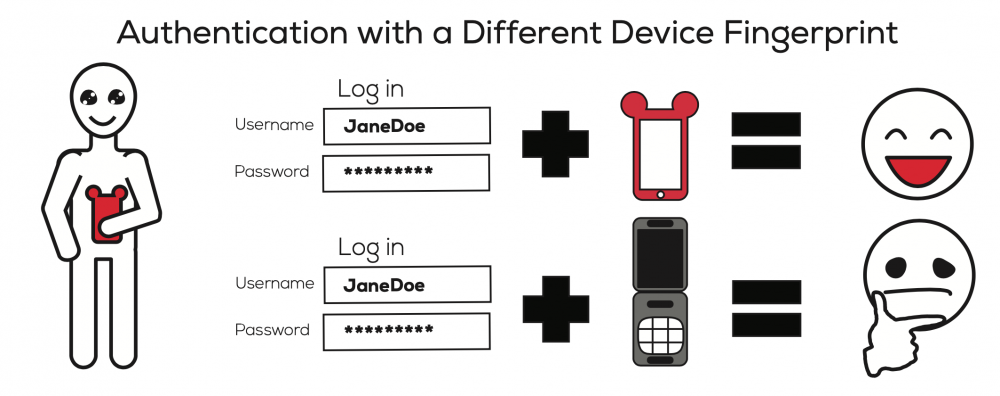

Web browsers explicitly or implicitly reveal device information to websites. Browsers explicitly share information such as the screen resolution, operating system or local time of a device. They can also implicitly provide other types of software or hardware information. All this information combined can uniquely identify a computer or smartphone; creating a kind of “device fngerprint.” Device fngerprinting is used for many purposes. For example, advertisers use device fngerprinting to track people online. The ability to uniquely identify devices means that device fngerprinting has the potential to augment existing online authentication methods; such as passwords.

Alaca and Van Oorschot looked at integrating device fngerprinting techniques into authentication methods without disrupting the user experience. They identifed and classifed 29 available device fngerprinting mechanisms. Most were known mechanisms and some were new. The researchers assessed how suitable and practical each mechanism would be for improving user authentication.

A good device fngerprint must contain a well-balanced combination of both reliable and distinguishable identifying characteristics. A reliable characteristic is stable and does not change, like model number or screen size. Because all devices of a particular model have the same fxed hardware, model-relatable specifcations alone are not enough to distinguish one device from another. Furthermore, if a smartphone model is only available in a certain country or zone, there could be a similar relationship between the model, location and time zone. Attackers can determine a portion of device fngerprints from the relationships between commonly shared characteristics. There are other details that are more distinguishable. Characteristics such as hardware sensor calibration or specifc browser settings are more random and harder to guess. However, many of these characteristics change. For example, these changes can occur after operating system upgrades. It is possible to improve fngerprint longevity by combining multiple fngerprint characteristics to create a scored level of confdence or trustworthiness. Since device fngerprints can change over time, a score based system would allow elements to change while still identifying the device.

The researchers also identifed different threats based on the assumption that an attacker would eventually learn the properties of a device fngerprint. They then determined how device fngerprinting would hold up against different attacks. When used to augment passwords, device fngerprinting can completely stop conventional password-guessing attacks. It can also reduce the success of password and fngerprint guessing attacks. However, it can be more diffcult for device fngerprinting to protect against targeted attacks in which the attackers have device-specifc information. Phishing attacks that capture both the password and certain aspects of the fngerprint are also problematic. These attacks are less likely to succeed if the device fngerprint consists of multiple, variable characteristics. Finally, if an attacker hijacks an existing session, they may easily retrieve the device fngerprint. Fingerprints should therefore be diffcult to forge and used to authenticate sessions not only once at the beginning, but also multiple times throughout.

Fingerprinting has the potential to strengthen user authentication. Using multiple carefully chosen characteristics for device identifcation makes it more possible to identify the device in a way that is diffcult to guess. Device fngerprinting mechanisms do not require additional attention from device users and seem to pose no additional usability burden. Consequently, they offer promise as an additional factor for authentication.

Fingerprinting as an additional factor has the potential to strengthen authentication.