The use of online services to meet romantic partners has facilitated the emergence of a type of online crime referred to as Romance Fraud. Criminals develop romantic relationships with people for the purpose of extorting money from them. Research shows that Romance Fraud is widespread across the world. In 2016 alone, the Canadian Anti-Fraud Center (CAFC) received 831 reports of romance fraud cases, with a total loss of more than $20 million. The CAFC estimates that only 10 percent of actual cases are reported. Even in spite of the damage it causes, support services for romance fraud victims are rare.

Cross, Dragiewicz and Richards reviewed the limited research on romance fraud together with that on domestic violence. They aimed to highlight key aspects of psychological abuses in a domestic violence context that could help understand romance fraud. They also interviewed romance fraud victims to gain insight into the non- violent techniques used to compel the affected people to comply with demands for money. By looking at the dynamics of influence in romance fraud, Cross et al. hoped to uncover new information on non-physical abuse in a domestic violence context.

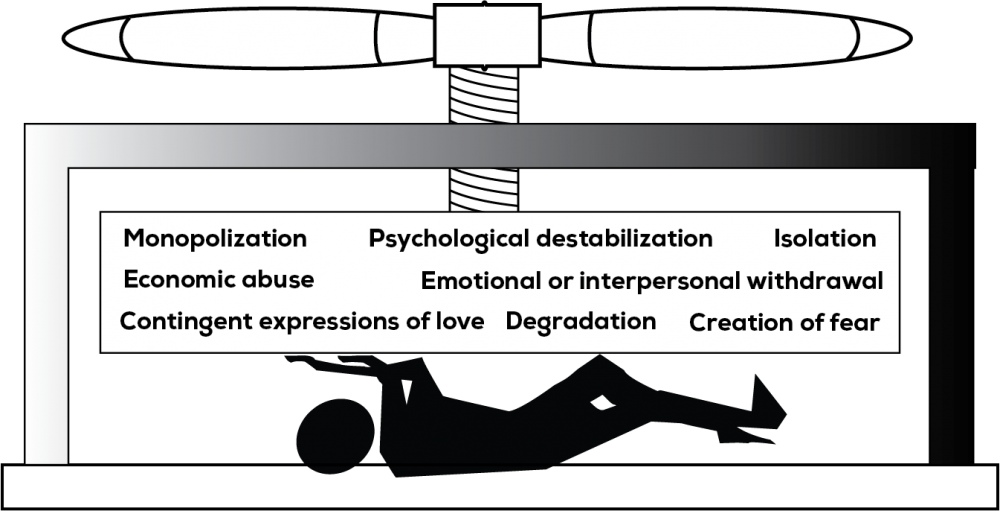

They interviewed twenty-one victims of romance fraud that were identified in a 2016 study on the experiences and support needs of online fraud victims in Australia. 80 online fraud victims had reported losses of AUD$10,000 or more to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s ‚‘Scamwatch’ website in 2016. The researchers interviewed romance fraud romance fraud victims from this group. They analyzed the interviews using nine categories of psychological maltreatment.

There appeared to be a significant overlap between romance fraud and domestic violence cases. Eight of the nine psychological maltreatment categories were found in the interviews. None of the interview subjects had experienced rigid sex role expectations or trivial requests. The key difference between domestic violence and romance fraud was the absence of physical violence in the romance fraud cases. This was likely due to the fact that romance fraud offenders are usually based overseas. In the absence of physical violence, Cross et al. observed that offenders used a mix of positive and negative forms of manipulation to control the victims. Some interview subjects still reported experiencing fear of being victim of physical violence during their romance fraud relationships.

The authors noted that romance fraud victims are often perceived as being responsible for their circumstances. They suggested that clarifying the presence of psychological maltreatment in romance fraud could help victims access a genuine victim status, which is critical in obtaining services and criminal justice support.

Romance fraud has a great financial and psychological impact on victims and it deserves to be treated seriously.