A password-strength meter judges how a user-chosen password will stand up to a hacking attempt. On many websites password-strength meters show the user a visual or verbal cue for the relative strength of their password. The intention is to lead the user to select a more secure password. Few password-strength meters provide any explanation of how they evaluate passwords, but common criteria include length, complexity, use of common words or easily typed sequences, and matches to user personal information.

de Carnavalet and Mannan tested 4 million common passwords using the meters from 11 different popular websites covering a range of financial, email, cloud storage and messaging services. The common passwords used were taken from dictionaries leaked from hacked websites and other lists of frequently used passwords, and are also the ones attackers are likely to test.

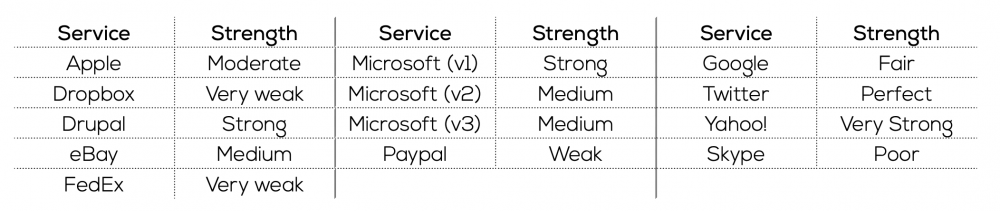

Each of the 11 websites uses a different meter, most of which rely on simple rules. Few of the password- strength meters included an algorithm to detect patterns and minor or predictable changes. None of the meters used the same set of labels to denote the strength of the password. Further, some of the programs did not enforce strength requirements by rejecting poor passwords, but only informed the user of the relative security of their choice. Because of the variation across meters, the same choice can be rated differently depending on the platform. For example, the choice of `password$1` is rated as follows in each of the noted systems:

There are also inconsistencies in the results from a single meter. That is, the rating assigned sometimes changes when the same password is attempted at different times, or the rating might change significantly for minor revisions to the password that may not actually reflect an improvement to the security of the choice.

Inconsistent results might cause confusion. A user creating a password could be misled by the meter’s response to their password choices – either to believe their weak choice is a strong one or that an otherwise strong password is judged as inappropriate. If users do not understand the rules or how they are applied, they might be less willing to comply with the guidelines, or inclined to find a work-around that satisfies the password-strength meter, rather than selecting a truly secure password.

One part of the solution is for users to understand what makes a secure password and apply those standards in their own choices. The judgement of a password-strength meter should not be taken as a final verdict. Rather than placing the burden solely on the user, however, more rigour could be applied in existing meters and in the design of new systems, to support and reinforce choices that actually increase security. Thorough password-strength meters go beyond character complexity and length rules to consider patterns and common passwords from leaked lists, other languages and cracking tools. Those designing password-strength meters don`t need to start from zero; the open source meter implemented by Dropbox is available to be adapted and applied.

Password strength meters are a helpful tool that can reinforce good password choices but the current inconsistency between service providers sends mixed messages.